Some international students at VU Amsterdam speak of feeling excluded or separated, both within and outside of the classroom. This could represent a thorn in the side for a university that is striving to be inclusive.

Maybe you have already come across whispers of ‘no international’ happenings on campus. Such a phrase conjures up images of the United States during segregation or Apartheid South Africa. In this particular case, the phrase pertains to international students not being or feeling welcome at social gatherings or student housing opportunities.

The VU Internationalisation Team of the University Student Council – VUnited – mentioned that they have heard from a number of students that there is a culture of exclusion or ignorance from Dutch students towards their international counterparts. Ad Valvas attended a meeting where members could speak about their experiences off the record and interviewed participants afterwards.

Selin Çakmak, a Psychology student from Turkey, says: “I think this is an issue that everyone is aware of, but it’s not talked about much.” She refers to it as an intimidating topic to discuss, and also emphasizes that the systemic separation she observes is not absolute: “This generalization does not apply to everybody.” Other students we spoke to also underscored that. There are undoubtedly Dutch students who are welcoming towards international students and not all international students feel that they are unwelcome.

Not invited in the first place

While we encountered troubling rumours about students being rudely turned away or even expelled from parties because they’re international, the internationals who spoke to us on the record experienced a different form of exclusion: not being invited in the first place or simply not feeling welcome.

Çakmak speaks of a strict separation between Dutch parties and parties for international students. “The Dutch students are in one building and the international students are in a building across from it.” She states that there is a profound rift between the two groups, albeit with one notable exception that she describes as a neutral zone: “The best thing at Uilenstede used to be Il Caffè, because that spot was a melting pot of everything.”

She did attend a Dutch Party once. “It was quite an interesting experience. From the moment I entered that flat, it was like I was in a completely different dimension. People spoke Dutch, listened to Dutch music and whomever I tried to talk to said hi, but when they realized I didn’t speak Dutch they subtly left the conversation.” Based on her examples and the accounts from a few more international students, it appears that Dutch students can find it challenging and tiresome to engage in English conversations. “It’s also not my native language”, remarks Çakmak.

‘I guess they purposefully organized it in a way so that only Dutch people would come’

Lina Nasser, an Information and Communication student from Germany, says that there is a clear divide between Dutch and international students in her study programme. “When we were still on campus, they would be talking in Dutch and I can understand Dutch quite well. They would schedule all these parties for new Dutch students. Even though they didn’t explicitly say ‘no internationals’, they did not invite any of us. It’s not direct discrimination I would say, but I guess they purposefully organized it in a way so that only Dutch people would come.”

Separate housing

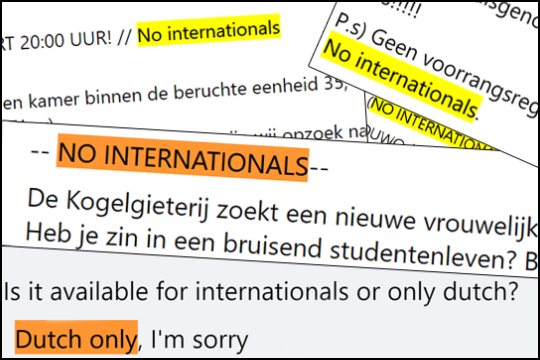

It’s something of an open secret – if it’s a secret at all – that international students aren’t always welcome in student apartments. The phrase ‘no internationals’ is especially common and, indeed, sometimes even prominently displayed in housing advertisements. This goes some way to explaining why the housing provider DUWO asked Uilenstede residents to be more inclusive towards international students. It seems that this form of exclusion is a routine occurrence across the Netherlands, inspiring research and various memes.

Selin Çakmak says she applied for many viewings in ‘Dutch flats’, but was never invited. “What they sometimes used as an excuse is that they weren’t able to invite me for a viewing because I’m not a Dutch student and therefore not eligible to live there.” Although she originally thought that this is true, she later found out that she is allowed to live there provided the students accept her.

Lina Nasser recounted an especially harrowing experience. She looked for student housing at Uilenstede while still living in Germany, traveling back and forth to attend viewings. She came across several advertisements explicitly stating ‘no internationals’. “It is really discouraging when you want to go to another country and it seems that you’re not welcome.”

‘I don’t think you will fit into this place. Your Dutch is kind of bad’

She did come across one advertisement for a place in a ‘Dutch building’ at the Uilenstede campus, which included an English translation. She responded in flawed Dutch and was subsequently invited to a group viewing.

After having drinks, they all sat in a circle and introduced themselves to each person living there. “They were exclusively speaking Dutch, because I was the only international student there, I guess.” Nasser attempted to speak Dutch, although this was a struggle for her. “When I was halfway through, I had a problem because I couldn’t think of a Dutch word, so I said it in English. The guy who I was talking to just looked at the others and everyone went silent. They said ‘You know what, I think you can leave now’, only to me.” Nasser paraphrased their explanation: “Sorry, I don’t think you will fit into this place. Your Dutch is kind of bad and it’s good that you’re trying, but we don’t really feel comfortable living with you like this.”

Traumatizing

She refers to the situation as “kind of traumatizing” and disheartening. “It was my first interaction with other students, and Dutch students in particular.” While she isn’t necessarily upset that she wasn’t selected to live in the flat, she finds it misleading that their advertisement included an English translation. She also finds the manner in which they rejected her rude and extreme.

International students also encounter obstacles in the classroom or on Zoom. For example, Lina Nasser refers to being placed in breakout rooms, where she awkwardly listens to students speaking in Dutch. She also noticed that Dutch people tend to prefer to work in groups with other Dutch people. While she understands that some students prefer to speak in their native language, “Still it would be nice to have a bigger sense of community. I think it’s a prevalent issue in basically every aspect of university life.”

Feeling like a party pooper

Nasser talked about the issue with professors, who according to her were also cognizant of the divide. They have attempted to do something about it by organizing informal get-togethers. However, attendance at these events tends to be low and some students respond quite negatively to them. “It’s not really possible to force people to interact”.

Another issue Selin Çakmak raises is teachers sometimes speaking in Dutch during an English course. “If it’s an English course, even if none of the international students showed up to class that day, the teachers should conduct the class in English. Because they can’t be sure that no international students are present, especially in big classes.” Leaving it up to international students to interrupt isn’t ideal, as Çakmak says that a student can feel like a ‘party pooper’ when asking the teacher to speak English. “It’s difficult for a student to stand up for themselves and once again remind the whole classroom that they are a minority who bothers the majority.”