“These days, even seven-year olds know what a sixpack is”, says philosopher of sport Ivo van Hilvoorde. He researches how our views on physical fitness have changed over time, working at the Faculty of Behavioural and Movement Sciences of VU Amsterdam and as a professor of Human Movement, School and Sport at Windesheim University of Applied Sciences. One of his conclusions is that a trained body has become a status symbol. “A body like that conveys the message that you’re disciplined, as well as able to resist temptations and take proper care of yourself.”

The body is the showroom of Me, Inc.

Working on your body has become a new religion. “People are younger and younger when they start working out”, says Van Hilvoorde. “Standards on physical fitness are omnipresent because of images on social media.”

In their 2008 book Fitter, harder & mooier (Fitter, harder & more beautiful), Van Hilvoorde and Ruud Stokvis described how individual workout routines became central to our culture. Over the past few years, the importance of having a toned, muscular body has only increased. Conversely, tolerance of bodies that don’t meet this standard has decreased.

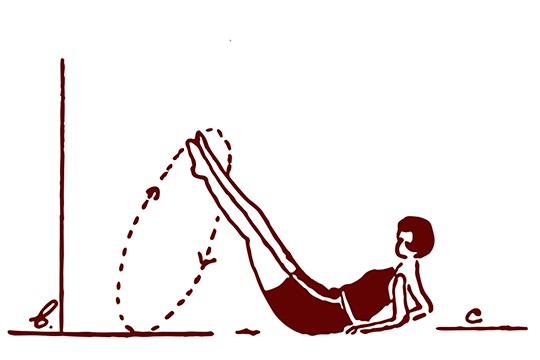

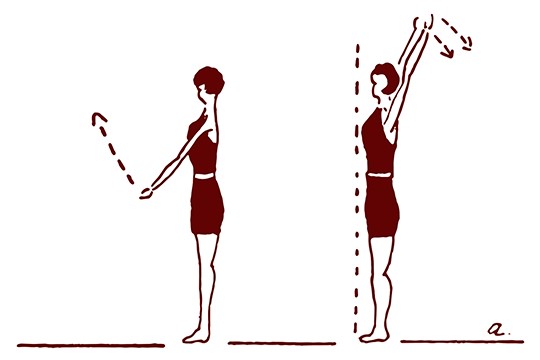

But this normativity when it comes to physical fitness isn’t new. Sport designed to make the body stronger and more beautiful came into being in the second half of the nineteenth century, write Van Hilvoorde and Stokvis. What was known as Körperkultur attached a great deal of value to the healthy, natural state of the body. For women, this natural state coincided with the beauty ideal: gymnastics clubs were founded so they could train their bodies to look shapely and graceful. The book quotes physician August Allebé, who in 1857 described the use of gymnastics for a young woman as a means to cultivate ‘tall yet curvy forms that were well-proportioned, a rosy complexion, a lively look in her eyes and a spring in her step’.

Gymnastics, corsets and diets

Technological innovations, such as the invention of the lightbulb, train and car, meant people had more time and could travel further to exercise. In social terms, sport developed from a local pastime to something to compete in on an international level.

Nonetheless, sport generally remained an activity for the happy few throughout the nineteenth century. Only after the Second World War sport clubs started enjoying greater popularity. It mainly concerned team sports, like football and korfball. It was at that time that the norm of having a slender figure – for women – spread to the population at large. This could be achieved through gymnastics, corsets and diets.

‘Runners got called names and laughed at’

The seventies saw a rising interest in individual sports and training the body to meet the beauty ideal. Urbanisation, individualisation and secularisation of society played a part in this.

“Fitness trends made their way here from America, in particular California, where stars like Jane Fonda and Arnold Schwarzenegger became figureheads of the individual fitness culture”, says Van Hilvoorde.

Running as a sport also started to become more popular, although joggers were still a far cry away from being accepted in the streets. “They got called names and laughed at, including men at first, although they could get away with more than women”, says Van Hilvoorde. The footage of an organiser of the 1967 Boston Marathon trying to physically drag first-ever female competitor Katrine Switzer out of the race says it all.

Gyms where people work on their bodies in a structured manner became immensely popular in the nineties. At first, men focused on growing muscles by hitting the exercise machines, whereas women worked on their figures through aerobics and related group lessons. After a while, this division became less rigid. Nowadays, working out is as ingrained in modern city life as the oatmeal cappuccino.

Unwillingness to fund unhealthy behaviour

“A good-looking and fit body has increasingly become a form of social capital”, Van Hilvoorde asserts. We associate good looks with health and success. And the degree to which you achieve those looks is thought to be your own responsibility. This is the root of the problem. “The body is the most visible expression of how we’re doing. It brings to the fore all kinds of factors that have to do with our socio-economic status, health, well-being and position in society.”

Working out and other forms of exercise have a meritocratic image: your success depends entirely on your own effort and discipline. But according to the philosopher of sport, this is a misleading and elitist ideology. After all, not everyone can free up enough time, energy and money to achieve a well-trained body.

Which is why he thinks it’s an oversimplification to suggest more exercise is the ultimate solution for issues that are expressed by the body, such as obesity and related disease patterns: “You can stress the importance of sport and exercise all you want − and some of my colleagues do − but if people have a whole range of complex underlying problems, such as too little money to buy healthy food or too many worries to have any energy left to work on their fitness, you’ll first need to recognise those problems. In that case, the body is the place where these issues are most visible, but the cause is somewhere else.”

Tolerance of people whose bodies do not meet the standard has decreased

Statistics Netherlands calculated that on average, higher-educated people have fifteen more healthy years than the lower-educated, poorer part of the population. This distinction grew more pronounced in the past years, whereas tolerance of people whose bodies do not meet the standard has decreased.

“Society has become stricter”, says Van Hilvoorde. “The neoliberal vision of everyone being responsible for their own health has grown more and more dominant. I often hear people say they don’t want to fund someone else’s unhealthy behaviour. This means every individual is responsible for their own health, but the question is whether that’s really fair.”

Working at the idealised image

As early as the nineteenth century people didn’t only work out for their health, but also – and perhaps especially – to be found attractive. In that sense, those nineteenth-century gymnasts are not that different from modern-day influencers. What is different, is that the standard of what constitutes good looks has become narrower. The rise of social media and the wide range of cosmetic possibilities play a part in this. Straight white teeth, a smooth, tight skin, a slender figure with round breasts and buttocks (women) or the famous sixpack (men) have become the standard. Is that harmful? Van Hilvoorde thinks it is, to some degree: “Research shows that young people feel increasingly forced to meet this standard. This already starts with teenagers, who have strict ideas about what looks good and what deviates from the norm. That’s not always good for their self-image.”

At the same time, the idea of what an ideal body looks like is growing more diverse, for instance when it comes to gender. “Our ability to modify our bodies through technical interventions and surgeries is increasing, which adds diversity to our perception of the ideal body.”

All the same, this means the body is no longer a given, but an object that must be moulded into the ideal image. Or to use neoliberal jargon: the body is the showroom of Me, Inc.

A fit body is a necessity to keep up with the quick pace

And for young adults, keeping this showroom in shape is piled on top of all those other obligations: getting good marks, working a side job, having a rich social life, etc. “I see it in students and young scientists. Some of them combine being a top athlete with a double Master’s programme, or a bunch of extra courses, all to set themselves apart.” Having said that, the philosopher of sport also considers the pressure that young adults are under as something that belongs to that phase of life: “When I graduated, there were no jobs. Now there are jobs, but contracts are fixed-term and homes are unaffordable. Every period has its own problems.”

What has changed, in his observation, is that the current generation of students is more concerned with what’s healthy: “They have a lot to do in little time, which is an extra stress factor compared to the old days. This turns a fit body into an instrument and a necessity to keep up with the quick pace. One could say that’s unhealthy, but the way students used to live, with lots of alcohol and pizza, wasn’t exactly healthy either.”

The illustrations have been taken from Encyclopaedie voor de vrouw, practisch handboek voor het dagelijks leven (Encyclopaedia for women, practical guidebook for daily life), edited by M. G. Schenk, De Bezige Bij, 1951.