As long as the best journals only have space for a fraction of the articles they receive as submissions, all academics will have to learn to live with rejection letters. Negative reviews are a cross researchers have to bear.

‘It’s scandalous that there are researchers who are so ignorant’. That’s a comment Katinka van der Kooij, psychologist at Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, once received from a reviewer. It’s always stayed with her, although she has had many more positive experiences with peer review than negative ones.

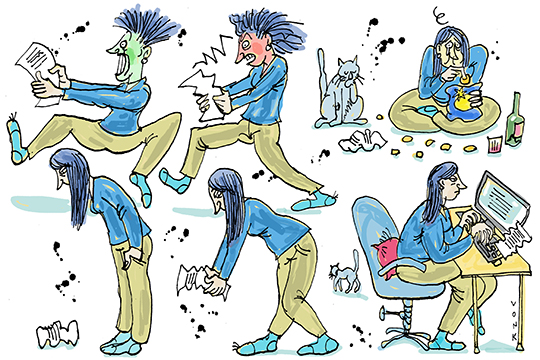

Take a deep breath, throw a couple of good punches at a punching bag, and carry on

Negative reviews are painful. And certainly if they are so blunt. But academics can’t escape them. Cultural researcher Maranke Wieringa of Utrecht University posted a tweet a year ago about the five stages of peer review: ‘denial, anger, bargaining, depression, acceptance.’ In other words, the mourning process. And that’s a process that every academic has to go through, because the better journals reject the vast majority of the submissions they receive.

> In recent years, double blind peer review is gaining ground, where neither reviewers nor authors know each other’s names. This means that an author’s prestige and background are excluded from influencing editorial decisions.

> The newest development is making the review process completely open. Open means that reviewers and authors both know who they are dealing with. Open reviews are a part of open science.

And when it happens, you have to take a deep breath, throw a couple of good punches at a punching bag, eat a whole bag of barbecue potato chips, and carry on. Because you’ll always find a place to publish your article eventually, the academics I talk to tell me. Only not in that one journal you were dreaming about.

Being rejected, therefore, goes with the territory, but it matters how it’s done. ‘Sometimes you get the impression that the reviewers suffer from a pathological correction obsession. They should give more constructive criticism: instead of ‘how can I split every hair’, ‘how can we turn this nice paper into a really sophisticated analysis?’, Jelle van Baardewijk, cultural philosopher at VU Amsterdam, tweeted in response to our call to share experiences with peer review.

The tone makes all the difference, Van der Kooij says too: “If you get a pleasant email from the reviewer, you’re more motivated to really improve your paper.”

Personal motives

Jos Akkermans, VU Amsterdam researcher in HRM and organisational behaviour, and editor of the Journal of Vocational Behavior, believes that a rejection always has to be based on good arguments. “As a researcher, I dislike rejection emails that say nothing more than ‘see reviews’, but it’s quite common.”

The most unsatisfying are the rejections that give you the feeling that personal motives played a role, the interviewed researchers say. “For example, if someone gets really angry because you didn’t cite a certain article. You think to yourself, that’s probably the reviewer”, says Willem de Haan, VU professor of criminology. Sometimes De Haan has had the feeling that the reviewer had an axe to grind with him: “You can’t ever be sure because the procedure is anonymous. But the number of Dutch researchers who are engaged with this topic is very small.”

‘I have a somewhat fatalistic view’

De Haan got some really brutal reviews when he submitted a book proposal on the topic of holocaust studies. “My proposal would be insulting and cause pain to the survivors. The message was: this isn’t your field.”

De Haan believes that peer review calls up all kinds of negative human responses: “Pettiness, territorial behaviour, exclusion and bad luck. I have a somewhat fatalistic view: you win some, you lose some. And you can’t do so much about it.”

Back up criticism with reasons

His colleague law researcher Klaas Rozemond thinks that submitters have a right to know how things stand. Rozemond is VU confidential counsellor for academic integrity. He believes that Dutch academic journals need to better codify their procedures for rejecting an article. Who can you appeal to? Do the editors have to provide reasons for their decision? “The big international journals have fixed procedures for this, but the Dutch journals often don’t”, he says.

Rozemond ran into this problem himself last year when he wanted to publish in the Nederlands Tijdschrift voor Geschiedenis. In his paper, he defended the proposition that, in legal terms, the holocaust was a genocide. The reviewers thought the paper wasn’t sufficiently embedded in the historiographical discussion. “But I didn’t want to write a historical article, I had a legal story that I thought would be interesting for historians”, Rozemond says. The editors initially thought Rozemond’s proposal was interesting. But the reviewers rejected it. And then the editors decided not to publish the article and only pointed to the reviews. Rozemond disagreed and wanted an independent judgment from the editors, but they kept invoking the negative reviews.

Academic integrity

The same article did get published in Delikt & Delinkwent, but Rozemond had wanted to publish it in a historical journal because he thought his line of reasoning would especially interest historians as a new approach.

After getting the rejection, Rozemond went first to Leiden University’s committee on academic integrity where the chief editor works; they declared his objection unfounded. Afterwards he approached the National Board for Research Integrity (LOWI). LOWI also eventually told Rozemond that he was in the wrong, but asserted that the editors of an academic journal must follow the Netherlands Code of Conduct for Research Integrity and have to check whether the reviews were written with the necessary due diligence and fairness.

Rozemond thought that part of the decision a win, but the rest disappointing.

Obscure jargon

Cultural philosopher Van Baardewijk objects in principle to the whole system peer review is part of. “Academic research is mostly paid for by collective funding and the results should therefore be for the betterment of our society. But the average academic article is read by 10 to 40 people. That’s very few. And, it must be said, these articles are often unreadable: badly written and full of obscure jargon. Everything revolves around niche journals that publish in English. Peer review is part of this compartmentalised system and keeps it alive.”

“Dutch academics have to publish in international venues”, Van Baardewijk continues, “which means that they throw themselves en masse at international, often American, topics that the important journals consider interesting, such as leadership. That means that typical Dutch topics get less and less attention. The consequence is that there is a paucity of relevant knowledge flowing back into our society.

Let all those academics who think that they don’t get enough funding explain to a wider public why what they do is useful.”

Generous colleagues

De Haan remains a supporter of the peer review system, but sees ways that it can be improved: “It’s important that you maintain an open mind as a reviewer, even when reading about topics that strike you as uninteresting. Be generous with your colleagues. Sometimes I read old reviews that I gave and I think, why did I make such a big deal about that?”

He thinks that it would help junior academics to learn under supervision how to write reviews, and to pay them for it too. Journals should publish a list of their reviewers each year, so that authors can put the reviewer’s name on their CV.

‘Sometimes it’s unclear why they asked you to be a reviewer’

Back to the current system where most academics prefer to publish in big English-language journals. These same academics are also reviewers. Sometimes they get twenty requests a week to evaluate articles. It’s all volunteer work. And the pitfall is, the better you do the work, the more often you will be asked to do it.

“If it’s totally unclear why they asked you, it’s really irritating”, says Akkermans, who refuses most of these requests due to time constraints. As an editor he therefore has to think carefully about who he is going to ask to review an article: is this topic really in his or her field? Akkermans makes use of his network, lists of references and sometimes Google Scholar to find the right reviewer.

Most submissions by far are not published in his journal. Sixty percent don’t even make it to the reviewer. The editorial board finds articles unsuitable if they are methodologically unsound or off topic. “There are huge differences in the level of sophistication, especially from countries where academic research is up and coming.”

When Akkermans rejects an article, he always takes time to consider how to formulate his rejection letter. Sometimes he gives the authors tips about journals that would likely be more interested in the article or how the author could rewrite it. “Often I put a lot of time into my work as editor. I average about thirty hours a week.”

Sometimes nice things happen during the review process, too. Akkermans: “It’s fantastic if you can see after several months of revision that the paper has really improved. That’s what drives me. Then all that time that you put into it hasn’t been for nothing.”

Embarrassing

Because ultimately, the whole purpose of peer review is to contribute to the progress of knowledge. Psychologist Van der Kooij: “My research often falls a bit between two different fields, which means that sometimes you don’t have all the literature in one area. If a reviewer points to something that I’ve missed, that only makes me happy.”

De Haan, too, says that his articles are frequently better because of the reviewers’ comments: “I remember that the reviewer pointed out an inconsistency between two parts of our article, and another time that we had completely missed some important research. Or when the reviewer pointed out an article that refuted our conclusions. That made things difficult for us, but it’s good for research.”