The Einstein Telescope is one of Europe’s biggest astronomy projects in the making. But why do we need it? It’s all about gravitational waves: the ripples in space-time Albert Einstein predicted with his general theory of relativity. These waves offer astronomers an exciting new way of observing the universe.

“When I started working in this field, there were people saying nobody will ever measure gravitational waves”, says Andreas Freise, project director and professor of Gravitational Wave Physics at VU Amsterdam. “But science succeeded in the first detection of these waves eight years ago, which was fantastic. Now, we want to see more because we’ve only seen the tip of the iceberg – and that alone was already very interesting. The current detectors Virgo and LIGO, however, were built for discovery and not for extensive research. The real stuff happens when you have a better signal – you can see further into the universe and you can see more details. To do that, we need the Einstein Telescope.”

Waving your arms

To understand how the Einstein Telescope will work, it’s necessary to understand the nature of gravitational waves. They can be seen as vibrations of space-time, which is the underlying elastic fabric on which everything in our cosmos takes place. Gravitational waves are caused by extreme events in the universe, such as massive stars or black holes that collide. Because space-time doesn’t change its shape very easily, enormous amounts of energy are needed to distort it. “When I wave my arms, the distortion is so weak that we can never measure it”, Freise says. “But if something very large waves its arms, then we have a chance.”

‘Hearing’ the universe

Traditional astronomy uses electromagnetic radiation to do measurements, such as light or radio waves. Gravitational waves, on the other hand, are a new way of looking at the universe. Or, as VU professor and former Einstein Telescope director Jo van den Brand put it in an interview with news source NOS in 2016: ‘It’s like being in a concert hall and suddenly not only seeing what’s happening on stage, but being able to hear it as well.’

The Einstein Telescope will “hear” more than ten times better than current detectors. What can we discover with such increased sensitivity? “At small distances, you can suddenly detect weak signals. And the stronger ones, you can detect from much further away”, Freise explains. “That means that the Einstein Telescope can look back in time, almost to the point of the Big Bang – the beginning of the universe.”

When stars weren’t born yet

Back then, stars weren’t born yet. “If you assume that black holes arise from dead stars, you wouldn’t expect to find any black holes. If we do detect them, that means they could have emerged without forming a star first. These primordial black holes, as we call them, could help us with the dark matter mystery, as they might be a form of dark matter we haven’t expected.”

With the telescope, researchers will also test Einstein’s general relativity. “We know it can’t be fully correct because it doesn’t match quantum mechanics. Maybe the Einstein Telescope will give us new insights.”

Time machine

Can you look back in time with a telescope? Well, sort of! A simplified explanation is that light takes time to travel from one place to the other. So when we look at a galaxy that is one billion light-years away, the light that we observe took one billion years to reach Earth. By looking at beams of light – or gravitational waves for that matter – we can thus infer what a galaxy looked like millions or billions of years ago.

The Einstein Telescope might also yield totally new findings, things we could have never imagined. “The first time people looked at galaxies with radio waves, they could see superstructures in the universe with filaments [threadlike structures, Ed.] connecting galaxies. I would be really surprised if we didn’t find anything strange with the Einstein Telescope. You just don’t know what you don’t know.”

Extremely sensitive

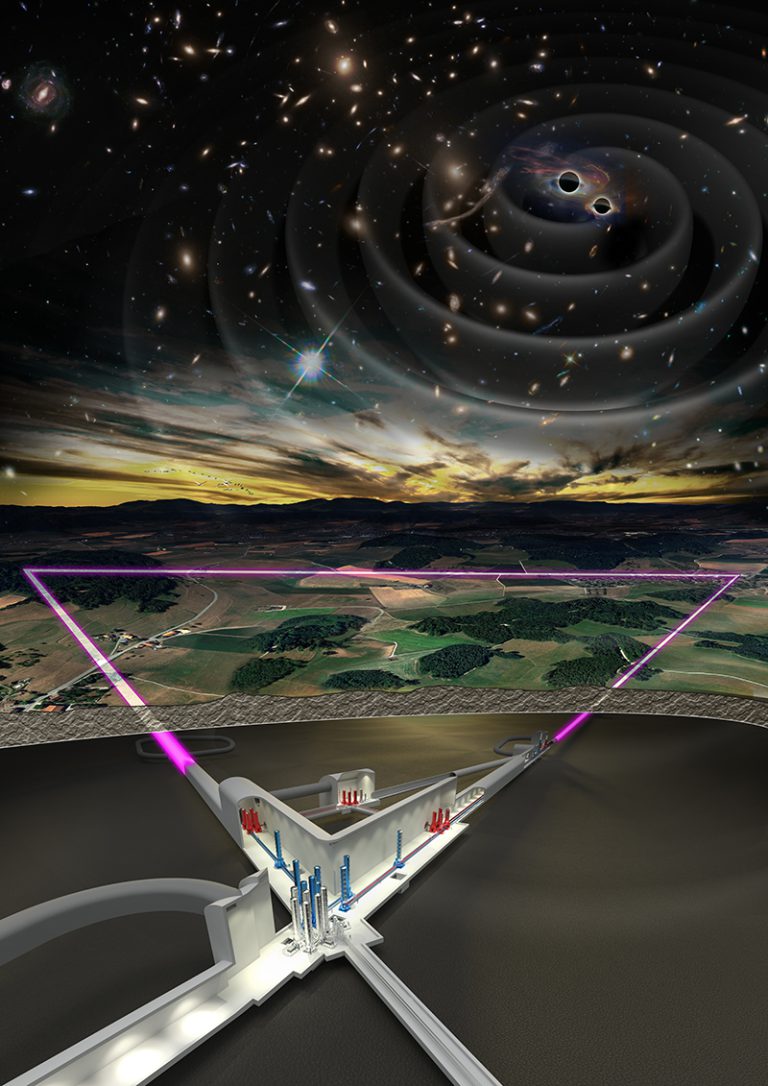

But how exactly will the Einstein Telescope measure these events? When gravitational waves ripple through the universe, the distances between objects expand and contract by minuscule amounts. Humans cannot perceive these ripples, but very sensitive instruments like the Einstein Telescope can. It will be able to detect differences in distance 10,000 times smaller than the size of a proton, which in turn is 100,000 times smaller than an atom.

The Einstein Telescope will consist of three triangle-shaped vacuum tunnels of ten kilometers long each. A laser beam is injected into these tunnels and reflected back by mirrors to its starting point. When a gravitational wave passes, space and time are stretched. “This means the tunnels stretch, but we can’t see that. What we can see is what the mirrors do. If they move due to a gravitational wave, this changes the laser beam, which we can measure.”

The suitable soil of Limburg

To be able to measure the tiny movements of the mirror when a gravitational wave hits, the telescope itself should be free of vibrations of its surroundings. And for that, it’s better to go underground. “The Earth is always moving a little bit from earthquakes, ocean waves and people. These disturbances are much less below ground. The wind is another factor: it pushes against a building and the building shakes the ground. If you’re underground, you don’t have that.” Luckily for the Dutch, the soil of the Southeastern tip of the Netherlands happens to be quite suitable for this kind of setup.

The battle is on

There are two reasons for this. First, the top layer of the soil in South Limburg is relatively soft, which dampens vibrations from the surroundings. The hard rock layer underneath on its turn seems perfect for drilling the tunnels. To ensure the soil is indeed suitable for the Einstein Telescope, geologists will be doing measurements over the next two years.

The proposed location for the telescope is close to the three-country point with Belgium and Germany. Freise: “It’s a joint project between these three countries and we would like to try to really make it a proper European project. The infrastructure might even cross borders.” Still, the three-country point isn’t the only viable location for the telescope. “My Italian colleagues are proposing for the Einstein Telescope to be built in Sardinia”, Freise says. “They received money to develop that idea and they are doing comparable geological investigations.”

Millions of euros

The Dutch government seems determined to bring the Einstein Telescope to its region. Last year, it invested 42 million euros in the project through the National Growth Fund. “We made the case that if the Einstein Telescope were to come to the Netherlands, we would bring a lot of jobs, high-tech needs and media attention to the region. It would also attract plenty of talent to the Netherlands”, says Freise. The 42 million euros are used for preparatory work, such as innovation of the required technology, location research, and setting up the organization behind the project.

The Dutch government also put aside a staggering 870 million euros to actually build the telescope if it comes to the Netherlands. “That would pay for the Dutch part because we estimate the total cost to be around 2 billion euros.” Freise, who lives in Amsterdam, wouldn’t mind the telescope coming to the Netherlands. “I could be directly involved without moving, which is nice. I also think the Netherlands has a big advantage due to the easy connection to other European countries. What I really like about CERN, the European infrastructure for particle physics, is that it is more than science. It is a place for Europeans to work together, sharing European values. I think that we could create something similar to the Einstein Telescope here in the middle of Europe.”

No elbowing

Despite the positive odds of the Einstein Telescope coming to the Netherlands, other countries – like Italy – are also working hard to get the telescope to their country. Since last year, Freise has been one of three project directors who have been trying to manage all these different efforts.

“You don’t want to have competition between teams for everything. You just want them to do their best work so that the best side wins. We try to coordinate what is already done by the teams locally and fill the gaps for what needs to be done together. For example, if you design a cooling system or establish rules for distributing electricity and water, they’re probably the same for different countries. It’s not something that local teams will be interested in doing, but you need these things to get the telescope approved.”

In addition, Freise and his team make sure that it is possible to compare the work of the different teams. “It’s really important that all the documents are harmonized, so that governments can understand them and make an informed decision on them.”

Life purpose

Being the director of such an enormous project is something new for Freise. “Most of us who live our normal lives are not really involved in these large projects. It’s comparable to motorway construction or building a new headquarters for a company. This project is quite a departure from my science experience, but it’s interesting to step into that zone and see something that I’m usually not a part of from the inside. That’s one of the reasons why I agreed on becoming the director.”

The current planning is that in 2025 or 2026, it will be decided where the Einstein Telescope will be built. If it doesn’t come to the Netherlands, would Freise be disappointed? “I’ve been working on ET since its beginning. I was part of this first small group of people that had the idea back in 2005. So for me, it was never about the Netherlands at the time, it’s about what science needs. I asked myself the question: what is the one thing that I want to achieve in my career? Well, I want the Einstein Telescope to happen.”