Shouts are frequently heard coming from the office of the senior professor of Cognitive Psychology. “Everyone knows about it,” says one scientist. ”But nobody says anything. We pretend it’s normal.” According to another, “He yells at people, swears, calls you stupid, ignores you for weeks on end and talks over you at meetings when he feels like it.”

Forty per cent of employees at Dutch universities experience a lack of social safety in the workplace, according to research published two years ago by trade unions FNV and VAWO. People from departments and faculties across VU Amsterdam responded to our call to share their stories. Most were hesitant. Some later pulled out, despite being able to speak anonymously. The fear of repercussions is well-entrenched in the academic world.

It was all the more remarkable, then, that we received three separate accounts from the same department: Experimental and Applied Psychology. Stories serious enough to warrant further investigation.

‘I often think about the newcomers’

To be sure that the stories carry weight, I approached numerous current and former employees of the department. Many of the latter say that the problems within it were the reason they left. Few of those currently employed there are willing to talk. Others are afraid, but let me know that they want to see an article published because they hope it will improve things. Because, they assure me, the atmosphere is still tainted.

About this article

This reconstruction is the product of several months of investigation by Ad Valvas reporter Welmoed Visser. She spoke with fifteen current and former employees of Experimental and Applied Psychology, and was in contact with more by e-mail. In addition, she reviewed official documents such as employment contracts, annual appraisal reports, e-mails and letters sent by departmental management.

By no means all the former employees are able or willing to cooperate, either. Two are not allowed to talk because of non-disclosure agreements with VU Amsterdam. Others do not want to because of the considerable psychological harm they have suffered, which has sometimes taken them years to overcome.

In the end, I was able to conduct interviews with fifteen current and former employees. I had only e-mail contact with a number of other people. One of those who did not wish to be interviewed did offer to read this article before publication. That was an opportunity I accepted, as a double check. Interviewees also reviewed the article and made corrections where necessary.

Those former employees who were willing to talk all did so for the same reason: so that their successors would suffer less misery than they did. “I often think of the newcomers who joined the group when I left,” says one. “Maybe I should have warned them, but I didn’t know how to.”

Dilemma

One dilemma has been whether to name the professors concerned. On the one hand, the reader is entitled to full disclosure and the men in question are all powerful figures within the university. On the other, this story is about the consequences of a long-lasting toxic social climate. We are interested more in exposing that culture than in naming and shaming particular individuals. Anyone wanting to know who is involved can easily find out, of course, but identifying them here would mean this story resurfacing every time their name was searched for, quite possibly forever. Ultimately, we consider that too damaging.

Ad Valvas considers social safety an important theme. Do you have experiences you wouldWould you like to share? E-mail usMail at: advalvas@protonmail.com.

The Department of Experimental and Applied Psychology (ETP) comprises three sections: Cognitive Psychology, Social Psychology and Organizational Psychology. The professors in charge of each have all been there for ten years or more. And together they have created a culture in which people often feel unheard, and sometimes intimidated. All the more so because two of the professors have taken turns leading the department, which has meant scientists being unable to approach the next person up the hierarchy with complaints about their immediate boss. “But you know what he’s like,” one was told when they finally dared to complain to the head of department (at that time the professor of Social Psychology) about the professor of Cognitive Psychology.

The problems in the three sections are not the same. In Cognitive Psychology, all our interviewees’ stories centre on the senior professor’s conduct. As far as we know, that is not an issue in Social and Organizational Psychology. What our sources there have great difficulty with is the atmosphere of “divide and rule”.

From their responses, it appears that the professors themselves are either in denial about their own behaviour or are unaware of how they are perceived as managers. “I may have a loud voice, but I don’t shout,” says the professor of Cognitive Psychology, even though we heard from various sources that he had yelled at them and at others. “I actually perceive the atmosphere in the section as very good,” we were told in an e-mail from the professor of Social Psychology, whereas we know that at least some of his employees do not feel comfortable there.

(Main article continues below box.)

The Department of Experimental and Applied Psychology comprises three sections: Cognitive Psychology, Social Psychology and Organizational Psychology. It has been headed by the professor of Cognitive Psychology for two years now. Prior to that, the professor of Social Psychology was in charge.

Cognitive Psychology has three professors in all.

Social Psychology has two professors, one of whom – the subject of this story – has led the section for some years.

Organizational Psychology has had a second professor for some time now. This story is about the senior of the two, who leads the section.

Until three years ago, Social Psychology and Organizational Psychology were one section. Since June this year, the Faculty of Behavioural and Movement Sciences has had a new Dean, Maurits van Tulder, whose background is in health sciences.

Back to Cognitive Psychology, where only last week we gained a direct insight into the tense workplace relationships. As a result of this article and the stress it was apparently causing even before publication, at the weekend an e-mail was circulated around the section by a PhD student. The heading, in capital letters: ‘Urgent, please respond before monday noon!’. The message urges staff to vote on whether they perceive the working atmosphere in Cognitive Psychology as ‘positive, open and inspiring’ – adding in so many words that the initiative is intended to generate a positive result to be submitted to Ad Valvas.

When the response evidently left something to be desired, a second e-mail followed with the same request. Again in capitals. On Monday we received an e-mail stating that the results were “not uniform” (not positive?) enough to use. Since then we have heard nothing more about this survey through the official channels. (Ad Valvas has copies of the e-mails concerned.)

Current and former employees have also been called by the section leader to ask whether they have cooperated with the Ad Valvas investigation. The question of who spoke to us seems to be occupying the powers that be more than the issues we have raised.

Rude comments

The behaviour of the professor concerned has long been known to his peers. Amongst them, the man is notorious for his bad manners. People applying to him for jobs are warned in advance by colleagues from other universities, albeit judiciously because the lines within the discipline are short and he is a successful scientist, a member of the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences (KNAW) and a past winner of numerous research grants. “Are you quite sure?,” one scientist who had applied to work with him was asked. “He can be quite passionate, you know”. Their response: “Passionate? I thought, that’s fine. So I am. If only they’d just said that he’s blunt, at least then I would have known where I stood.”

Two years ago the professor in question handed over day-to-day responsibility for the section to his number two, but he is now head of the entire Department of Applied and Experimental Psychology, still oversees his own group of about ten researchers and leads the Institute for Brain and Behaviour (IBBA), which brings together the work of seven research groups in the Faculty of Behavioural and Movement Sciences. He also continues to supervise a substantial group of young researchers, although according to our sources he does little to help them. “You have to figure everything out for yourself,” says one. “If you don’t know something, you’re better off asking colleagues because you can’t bother him with it. That really irritates him.”

‘There’s absolutely no room for your own input’

His comments on draft papers can be downright rude: “When you get an article back, it says in the margin: ‘What a stupid comment, sloppy work, you have no idea what you’re talking about.’” According to someone else, “At meetings he talks over people, makes fun of them.” And, says a third, “He wants you to do exactly what he has in mind. There’s absolutely no room for your own input. You’re his property.” Several scientists gave us examples, which are too specific to mention here because they could easily be traced back to the individuals concerned.

Around the professor is a small group of favourites who can do nothing wrong, but things are tough if you are not one of them. A simple request for travel expenses can be enough to make him explode (a specific but traceable example of this is known to Ad Valvas). Several scientists say that he ended up ignoring them completely.

In their experience, the professor believes that teaching is for losers. While he was still the head of the section, says one, there were no meetings about the educational programme for three years. The professor had no interest in organizing one: “He said he just didn’t want to hear our crap.” Eventually, the tutors arranged a meeting themselves.

But it also has to be said that the man is very successful as a scientist and so new, young researchers, mainly from abroad, are still eager to work for him.

‘I was shaking all over’

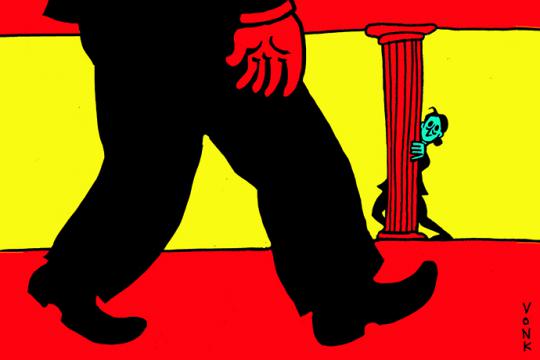

The consequences of his behaviour can be serious, though. Some of his employees have become overworked, some have needed therapy in order to be able to return to work and some have left science altogether. Above all, many have left his group. Those who have stayed in science sometimes encounter the professor at a conference, and then they feel the stress shooting through their bodies. “I was shaking all over and had to hide behind a pillar,” one recalls. “I never thought I’d react so violently.”

How is it possible for such behaviour to go on for so long? Have the victims not tried to seek help or mediation? Some have indeed gone to the confidential counsellor or the next manager in line, but they say that has been of little use to them.

You can lodge a complaint, the confidential counsellor told one person, but it will only harm your own career. A scientist who approached the previous dean was e-mailed a copy of the Inappropriate Conduct Regulations, but says that nothing further was done.

Job deception

In the department’s other two sections, Social Psychology and Organizational Psychology, the professors in charge are nicer to deal with. Yet here too there have been numerous conflicts over the years, and many employees have left under a cloud.

Until three years ago, these two sections were a single unit. Many current and former employees dealt with both senior professors and find it difficult to discern who exactly was responsible for what. The main thrust of their stories is that they feel deceived and left in suspense.

As an example, there are the four scientists recruited as “assistant professors” in 2012. They were introduced to the group in that capacity, were issued with business cards stating that was their position, were listed as such on the website and took part in research. (Documentation confirming this is in the possession of Ad Valvas.) Only after about four years did they discover – by chance – that they were in fact officially employed as “lecturers” (docenten), a position in which you are only supposed to teach, not conduct research, and with few academic career prospects. When VU Amsterdam decided in 2016 to post details of all its research activities online, one of the “assistant professors” noticed that their work was not included. A simple error, they thought, and reported the omission to their boss.

“Um, actually you’re only a lecturer and not a researcher,” they were then informed by P&O. A mistake, surely, the scientist still believed. But it was true: although they had been undertaking research work for several years, on paper they were employed only as a lecturer. All of a sudden, they noticed things they had never considered before. Their contract of employment, for instance, was in English but gave their job title in both English and Dutch: “assistant professor” followed by “docent” in brackets. The same turned out to be the case for the other three scientists employed at the same time; even though two had previously worked at prestigious foreign research institutes, none was officially an “assistant professor”. Would they have come to VU Amsterdam if they had known that? Never, they assert. What frustrated them most, though, was the handling of their case by management and HR: they had to play hard to press home their claim. Only when they threatened legal action were their positions retroactively converted to assistant professorships. (Documentation on this case is in the possession of Ad Valvas.)

Did the victims not seek help or mediation?

The professor of Social Psychology still seems unaware of the impact this incident had on those affected. “At the time,” he told us in an e-mail, “the distinction between assistant professor and lecturer was not always very clear.” In fact, it has always been crystal clear in the national University Job Classification (UFO) system. According to one of the victims in this case, “If I really had remained just a lecturer for five years, I could have waved goodbye to my academic career.” Which shows how different the professor’s perception is from those of the “ordinary” academic personnel in his section, people still fighting to build a career.

Even with this case behind it, the section tried the same thing again. A later applicant for a position as an assistant professor found that that was not the official job title in the contract they were offered. Having been forewarned about the previous problem, however, they were able to insist that the document be amended before signing it. The professors of Social Psychology and Organizational Psychology claim not to remember this second incident.

Missed opportunities

These cases are part of a pattern: a stream of stories of false hopes, half-promises and ever-changing demands in the Social and Organizational Psychology sections. The frustration amongst current and former employees is huge. Many of the latter have remained in academia and now work at other universities, in the Netherlands and abroad, where they see that things can be done differently. “At any rate I’ve learnt to be honest with my colleagues,” one of them says. “I try to give my staff opportunities, something I really missed at VU Amsterdam,” says another.

Several people describe the way the groups were – and are – led as a divide-and-rule model. “It was never completely clear what you had to do to make progress,” says one scientist. “The criteria were opaque and they changed fairly often. If you’d achieved your target number of publications, for example, then suddenly you had to score ‘excellent’ in your annual appraisal as well. And that was assessed by [the professors] themselves, who never awarded an ‘excellent’.” According to a former employee now in a permanent position at another university, “The requirements were unreasonably high, but I only realized that with hindsight.” Someone else says, “Once you’d fulfilled one norm, more criteria would always be pulled out of the hat.”

‘Once you’d fulfilled one norm, more criteria would always be pulled out of the hat’

People remember the manner in which their performance was appraised as very subjective, especially in Social Psychology. “On one occasion the form recording my performance review was lost,” recalls one scientist. “The professor said that he remembered what was on it and would fill it in again. When the original resurfaced, it turned out that I’d scored one to two points lower in every aspect on the form completed from memory.”

The procedures have since been tightened up. Managers are required to follow the faculty guidelines for staff recruitment and promotions. Yet people are still dependent upon the same professors for their careers – and after years of incidents, those we spoke to have little confidence that they are now being treated fairly.

Trust, cooperation and leadership

In Organizational Psychology, moreover, some scientists have little good to say about their direct collaborations with the professor. “When you supervised PhD students with him,” one comments, “he would sometimes not even have read the documents they had written. So it took you half an hour just to clarify things that were already in the text.” PhD students themselves also complain about their collaborations: it often takes weeks before they receive answers to e-mails and the professor makes little contribution to their research but wants his name on every publication.

Several members of staff in Organizational Psychology recall occasions when they felt that their ideas were being taken from them. One interviewee, for example, says that the professor used their idea to raise funding from a company without involving them. Someone else remembers the professor writing a blog about an article by another researcher in the group before it had been published.

Ironically, one of the group’s lines of research is what constitutes good leadership. For a long time, the title of the programme was Trust, Cooperation and Leadership (TLC). “We laughed a lot about that,” someone says. But the consequences were not so funny: staff left in droves. In the years after 2016, almost the entire Organizational Psychology section found new jobs elsewhere. Only with great difficulty was it able to sustain its teaching programme.

Nightmares

More personally, some of those who moved on still have nightmares when they face an annual appraisal interview. “I can stress about it for days,” says one former employee. “It feels like a sword of Damocles, even though I now work in a safe environment.” Another comments, “My new colleagues thought I was behaving like a beaten dog. That shocked me. I didn’t even realize how much it had permeated me.”

All three professors claim that the situation has improved since the department was restructured three years ago. In all three sections, we have spoken with people who disagree. The three men at their helms have all been there for many years. Cultural change, if any, is slow. But what has improved is the sensitivity of senior management. Even before this article was published, the Rector and the Dean of the faculty decided to initiate an independent investigation.

If their predecessors had done that earlier, a lot of suffering could have been avoided. Because for a whole generation of scientists in Experimental and Applied Psychology, there was only one way to protest: voting with their feet. Some are still baffled when they think back to their time at VU Amsterdam. “Only afterwards did I see that it really wasn’t normal,” one says. “I spent far too long there,” rues another. “I wanted to leave as soon as possible,” comments a third, “but I didn’t want to look like a job hopper.” Whilst they admit that things are not always a bed of roses at their new places of work, universities and research institutes in the Netherlands and abroad, in retrospect they all feel that VU Amsterdam could have taken better care of its employees. And that someone should have changed things.

I don’t recognize myself in your comments about my behaviour in meetings. If people feel that I’m ignoring them, it may be because I am no longer their direct supervisor, because I’ve given up the day-to-day running of the section. I am aware that mistakes have been made in the past with contracts and agreements in the Department of Experimental and Applied Psychology. Decisions were also made about employees which didn’t always match their expectations. That’s not good and I regret it. In retrospect, it can be concluded that there were a number of flaws in the structure of the department. Until two-and-a-half years ago, for instance, I was both head of the Department of Experimental and Applied Psychology and head of the Cognitive Psychology section. That caused all kinds of frictions and ambiguities. To overcome this, a few years back we appointed someone else as the head of section. My impression is that the working atmosphere is fine in all three sections, even in this time of coronavirus. There are regular lunchtime meetings, pub quizzes and colloquiums.

[This is a summary; the full response, in Dutch, can be read here.]

I was formally appointed as head of a new section in 2018. This is a small team, which focuses mainly upon education. In my opinion, this section functions pretty well. There has been hardly any staff turnover in recent years, apart from the departure of one employee who was not in the right place and another who found an obviously better position elsewhere. I do think that people without a permanent contract of employment may well be more dissatisfied. I can’t comment on any possible lingering dissatisfaction amongst former employees of the “old” section. Many of the problems identified by Ad Valvas date back several years, to the old section where I used to work. Amongst other things, these were the result of the incorrect classification of some employees as lecturers instead of assistant professors. Within the department, including in their annual appraisal interviews, these employees were treated as assistant professors. The mistake was eventually corrected by HRM and the head of department. In part, I place responsibility for that mistake on the old faculty, which set far too stringent requirements for securing a permanent position or a promotion. In my view, the suggestion that I read theses badly is unjustified. In accordance with the many-eyes principle, I look at and contribute to publications by PhD students.

[This is a summary; the full response, in Dutch, can be read here.]

I have never noticed any dissatisfaction in the section as it currently stands. Nor has anyone ever pointed this out to me. In fact, in my experience the atmosphere in the section is very good; for example, there is a lot of good cooperation between members of staff. And almost all PhD students complete their theses successfully. I can imagine that there is some dissatisfaction amongst some employees from time to time, because the opportunities for promotion or to secure permanent positions are limited. I often enquire informally (especially at one-to-one lunches, but also through “management by walking around”) and sometimes formally (at an annual appraisal interview) about all kinds of matters, and I have not noticed any unhappiness. In the past there was more dissatisfaction at the larger department in the old faculty, which almost exclusively affected people on temporary contracts with no prospect of a permanent appointment.

[This is a summary; the full response, in Dutch, can be read here.]

“There will be an independent investigation into the working atmosphere at the department. Social safety is an extremely important theme for me as Dean. I hope I display that, too. I take all signals I receive in this respect very seriously. That means that we respond immediately. Every complaint is in fact a situation in which you arrive late. You really want to be there earlier, to prevent things from escalating. I know it is a difficult and slow process to change the culture in this respect, but we need to get things moving. For that reason, I have for example already appointed a second confidential counsellor at the faculty so that people can approach someone a little more distant from their day-to-day-work. And every PhD candidate has to have a second supervisor. It is also important that we pursue a strict personnel policy, in which the principles and criteria are the same for and clear to the entire faculty.”

“Every complaint in the field of social safety is one too many, and we as the Executive Board take them all very seriously. In the case of this department, we must first explore exactly what is going on. We will be doing that through an independent investigation. I was not aware that something might be amiss in Psychology, otherwise we would have taken action earlier. VU Amsterdam has to be a safe and attractive place for staff and students to work and study. We want a culture in which people can safely hold each other accountable for their behaviour. But any culture change is slow. We try to achieve such change by paying explicit attention to it and by making the subject open for discussion. The appointment of confidential counsellors and the provision of bystander training are a couple of examples of concrete steps which have been taken. I know this is an important theme within the academic world. That 40 per cent of university employees do not feel safe at work [FNV 2018 – ed.] is far too high a figure. We have to have an ambitious goal in this respect: I fervently hope that in about five years’ time we will be able to write that percentage in single figures.”

Comments

For comments, please have a look below the original Dutch version of this article.