While camera surveillance makes some people feel safe, others experience it as an invasion of their privacy. According to the Dutch Data Protection Authority, an employer or educational institution must have a legitimate interest for camera surveillance. ‘For example, to prevent theft or to protect employees and visitors’, its website states. VU Amsterdam lists four reasons for camera use: prevention, detecting offenders, monitoring, and increasing the sense of security.

Deterring offenders

On its website, the university says the following about prevention: ‘Part of the preventive effect is of course achieved as a result of potential perpetrators being aware of the presence of the cameras and realising that the images can serve as evidence later.’ This sounds plausible, but is there scientific evidence for this claim? “There are studies that show camera security can be preventive, but context is important”, says criminologist Jasper van der Kemp. “If you use cameras to deter, you assume that potential offenders are paying attention to whether or not they’re on camera. And it also means those cameras have to be clearly visible. The funny thing is, I think 9 out of 10 people at our university can’t even tell you where the cameras on campus are situated. You barely see them, or you really have to pay attention.”

Incidentally, you can use camera surveillance in particular to prevent incidents such as theft, Van der Kemp continues. “Offenders often plan crimes such as theft. These calculated crimes you may be able to prevent, but incidents such as fights, for example, you cannot prevent with cameras. Those are typically things that happen as a result of emotional outbursts or under the influence of drugs or alcohol, although that doesn’t happen very often at VU Amsterdam.”

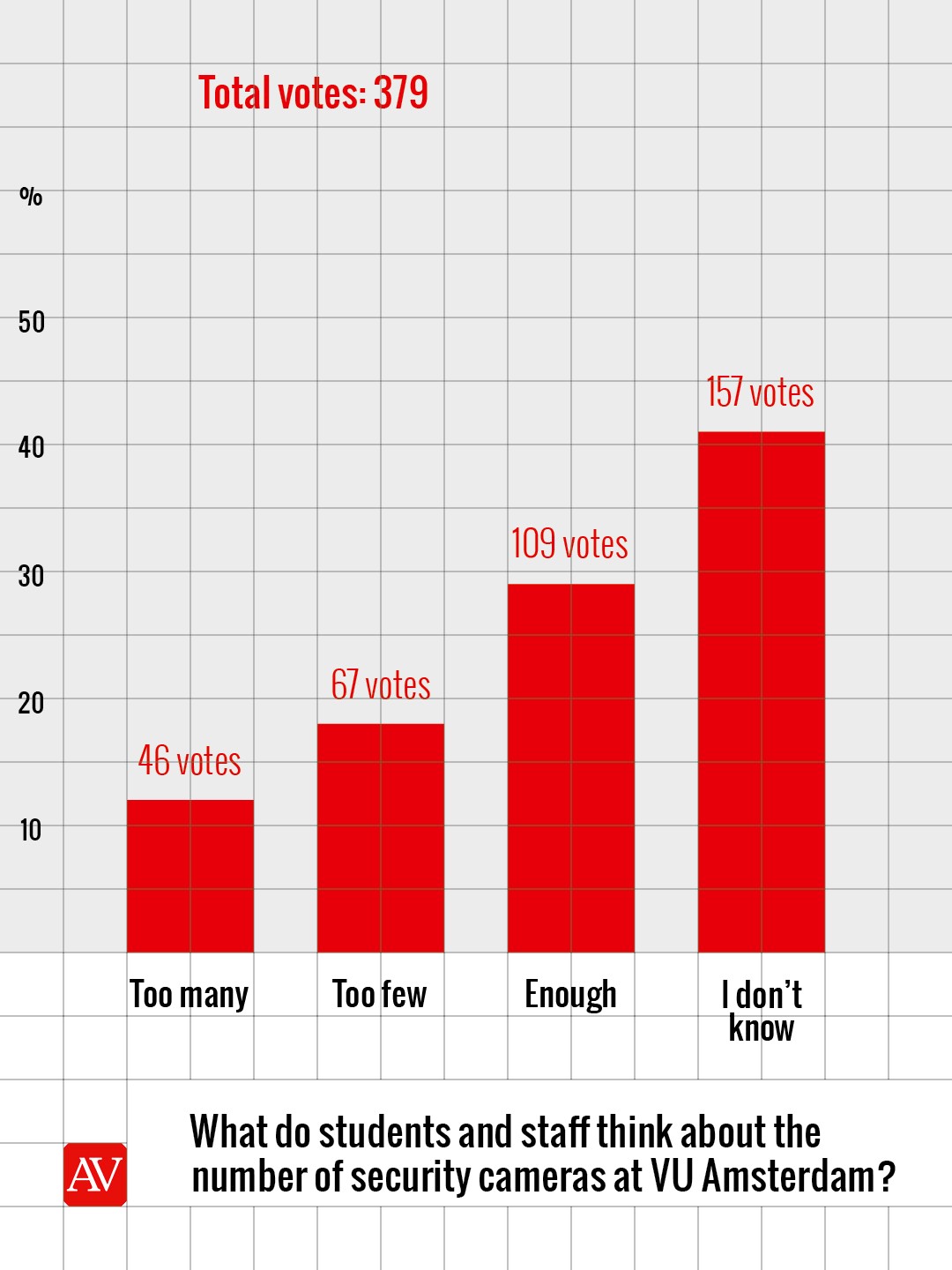

To a poll on Instagram, 379 people responded: 12 percent think there are too many cameras, 18 percent think there should be more cameras, 29 percent think the current situation is fine and 41 percent have no opinion.

To a poll on Instagram, 379 people responded: 12 percent think there are too many cameras, 18 percent think there should be more cameras, 29 percent think the current situation is fine and 41 percent have no opinion.

More measures at once

That leaves the question: is the deterrent effect such that offenders no longer strike at VU Amsterdam or do they look for a place where there are no cameras? Van der Kemp: “Proving a preventive effect is always difficult, but it has been demonstrated in some studies. Still, it’s hard to know whether camera security prevents many crimes at VU Amsterdam – you actually need a randomized controlled trial for that [An intervention study in which the study population is divided into an intervention group and a control group, ed.]. We also know from criminological studies that it is important to have more measures at the same time. So for example, a combination of camera surveillance, security guards walking around regularly, and students and staff keeping an eye on things.”

Hosts and guards

According to Corporate Real Estate and Facilities (FCO), VU Amsterdam is indeed using a combination of different measures. ‘We prefer to make use of our hosts and guards. But the campus is too large for surveillance alone’, FCO says in a written response. In other words, the university needs camera surveillance.

But what exactly happens to the surveillance footage? According to the Camera Surveillance Regulations, the images are kept for a maximum of 10 days – considerably shorter than the Dutch Data Protection Authority’s guideline of 4 weeks. FCO writes that there are clear agreements about reviewing the footage. ‘If we receive reports of incidents or if someone reports theft or violence, only a select group of people can view the footage. Therefore, it is important to report incidents as soon as possible so that we can find out if there is camera footage that should be stored.’

Hidden cameras

What stands out in the regulations is that the university has the authority to place hidden cameras. Does FCO actually deploy them? ‘We try to deploy physical alert surveillance first and only then visible cameras. We do indeed have the ability to deploy hidden cameras, but the VU Amsterdam campus is an open and welcoming environment where so far that has not been necessary.’ FCO is unwilling or unable to provide examples of when they would choose to deploy hidden cameras.

‘Big brother is watching’, a chalkboard reads in the New University Building. (Image: Emma Sprangers)

‘Big brother is watching’, a chalkboard reads in the New University Building. (Image: Emma Sprangers)

Constantly being filmed

When installing cameras, the university wants to avoid – as much as possible – people being continuously in view while working or visiting. The regulations state that there are also exceptions to this: ‘At locations where there are increased security risks, such as a relatively high risk of aggression or theft, it is possible that those involved are continuously on camera if this is necessary and when less drastic measures are not effective.’

‘For understandable reasons’, says FCO, it cannot comment on which locations are involved. ‘In the past, especially in the evenings, we have had several instances of molestation and vandalism in lecture halls. In such cases, active monitoring can enable quick and effective action. Signalling by fellow students is also a means of keeping the campus safe.’

Leaving laptops unattended

So VU Amsterdam also uses camera surveillance for monitoring. In the basement of the main building, security guards monitor the live images. In what other cases do they intervene? ‘In cases of extreme crowding, we perform crowd control’, says FCO. ‘The live footage enables us to see when it gets very crowded at an entrance. If that is the case, we open the revolving door or instruct campus coaches. That way we can keep everything on track.’

Finally, Van der Kemp mentions an adverse effect of camera surveillance. “If users of an area know that there is camera surveillance, they sometimes pay less attention to their belongings. For example, they are more likely to leave their laptops unattended. So camera security can also encourage unsafe behaviour.”