In the new collective labour agreement (CAO) for universities, reducing the number of temporary contracts is a major issue. Assistant professors in particular will benefit from this development. However, postdoctoral researchers will be no better off.

Trade union FNV argues that the new agreements on permanent jobs at Dutch universities indicate a “shift in culture”. In their role as employers, the universities refer to it as “a great step”.

But these new agreements have attracted criticism: most notably, who stands to benefit from the permanent contracts? Professors, associate professors, assistant professors and support staff can look forward to greater permanence. Other teaching and research staff are left in the cold.

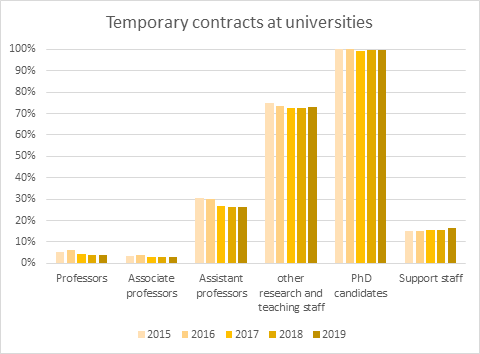

Eight percent of all professors have a temporary appointment, as do five percent of associate professors. These figures are exceptionally low. The new agreements on permanent contracts are not really intended for them.

The new CAO is aimed primarily at assistant professors, over 30 percent of whom were on temporary contracts five years ago, compared to 26 percent today. The unions are keen for this downward trend to continue.

© HOP. Source: WOPI figures, Association of Universities in the Netherlands (VSNU).

They have agreed, for example, that in future anyone who obtains a Vidi grant from the Dutch Research Council should be given a permanent position. This is particularly important for assistant professors, given that Vidi grants are intended for more experienced researchers.

But what about other teaching and research staff? “It’s true that we have been unable to do as much for them”, employers’ association VSNU tells de Volkskrant newspaper. The VSNU argues that this can only change if extra funding becomes available; the universities are currently campaigning for an additional 1.1 billion euros per year.

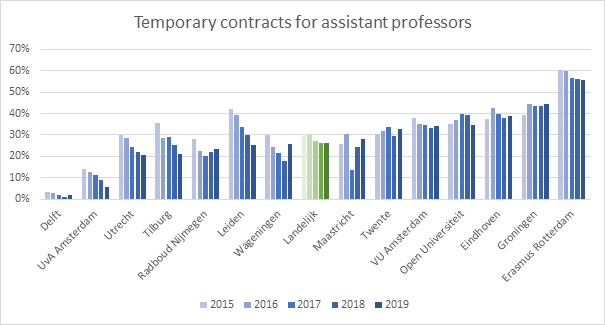

But if funding is the problem, why are the differences between universities so significant? At Delft University of Technology, for example, almost all assistant professors have a permanent position, while at Erasmus University Rotterdam 57 percent of them are on a temporary contract. It makes no sense to blame lack of government funding when the picture is so uneven.

© HOP. Source: WOPI figures, Association of Universities in the Netherlands (VSNU).

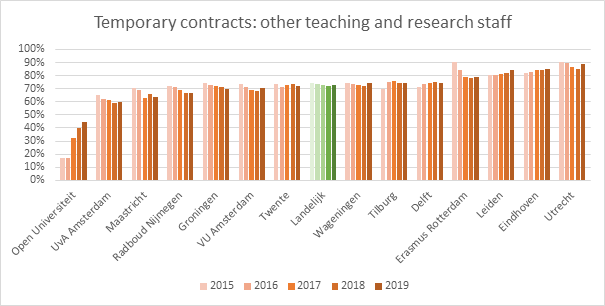

Similar differences can also be seen for postdocs and other teaching staff. At the University of Amsterdam, 59 percent of this group have a temporary contract: while this may seem high, at Utrecht University that figure is 90 percent.

© HOP. Bron: Source: WOPI figures, Association of Universities in the Netherlands (VSNU).

Such marked differences must be policy-driven. There may be good reasons for this policy, but the issue at stake appears to have little to do with the 1.1 billion euros that universities will or will not receive from the next government.

Especially when you consider what the current CAO has to say about postdocs, for example: “These are positions which, by their nature, justify the use of fixed-term employment contracts.” That is not about to change. Postdocs can still be offered a four-year contract, followed by a ‘qualified’ employment contract in which their job remains dependent on temporary funding.

And in the new CAO, ‘permanent’ will become a little less permanent. Permanent staff who lose their job in a reorganisation currently have ten-months’ protection in addition to three or four months standard notice. But that additional protection will be scaled back to three months by 2025.

The unions and employers’ association will now present the negotiated settlement to their members. The members then have until 1 August to give it their seal of approval.